May 29, 2003

Transmedia

Since 2002 - 2004 I have been a student in the Transmedia postgraduate program at Hogeschool Sint Lukas in Brussels, Belgium. The following entries are related to my work with archives during my final year, a project done in co-operation with Constant VZW.

to introduce the idea of stranding...

A complex of fibers or filaments that have been twisted together to form a cable, rope, thread, or yarn.

A single filament, such as a fiber or thread, of a woven or braided material.

A wisp or tress of hair.

Something that is plaited or twisted as a ropelike length: a strand of pearls; a strand of DNA.

One of the elements woven together to make an intricate whole, such as the plot of a novel.

To drive or run ashore or aground.

To bring into or leave in a difficult or helpless position: The convoy was stranded in the desert.

To separate (a grammatical element) from other elements in a construction, either by moving it out of the construction or moving the rest of the construction. In the sentence What are you aiming at, the preposition at has been stranded

June 10, 2003

November 10, 2003

mylifebits

looking into mylifebits

http://research.microsoft.com/~jgemmell/pubs/UEM2003.pdf

my first question is - affordable to whom?

'...a complete record of one's life.' what are the implications if one is removed from the system ( as the source of memory) is it the same as removal from a system of objects, such as a photo album?

see also:

http://www.iht.com/articles/90739.html

http://research.microsoft.com/barc/mediapresence/MyLifeBits.aspx

http://iu.berkeley.edu/rdhyee/2003/02/12

http://soreeyes.org/archives/000030.html

from human rights movements

"...the experience of the women's human rights movement suggests that a global feminism driven by international feminist networking is also possible. such networking does not require homogeneity of experience or perspective or even an ongoing consensus across a range of issues. rather it can be built around acknowledging diversity while also finding common moments at the intersection of diverse paths."- Charlotte Bunch in " Feminist Locations: Global and Local, Theory and Practice"

how can archives be included and utilised in this framework? (and what is the importance?)

November 11, 2003

selected bibliography

this is a space to record what i have been reading:

Dekoven, Marianne ed. Feminist Locations: Global and Local, Theory and Practice. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Eilean Hooper-Greenhill. Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture. London: Routledge, 2000.

February 23, 2004

some links to rdf, foaf info

Finding friends with XML and RDF

March 04, 2004

Proposal for an archive system

This system begins with a game*. It is based on encounters.

look into the archives box

choose something

find something which interests you about what you have chosen: it could be a memory, a question, whatever

find someone to share it with

record the subject of your discussion, the item, and the person you encountered into your online space

This game could take place during a specific workshop, or during several meetings. It is important that the first game be played between people in physical proximity. The online space will become home to the encounters made during the first game.

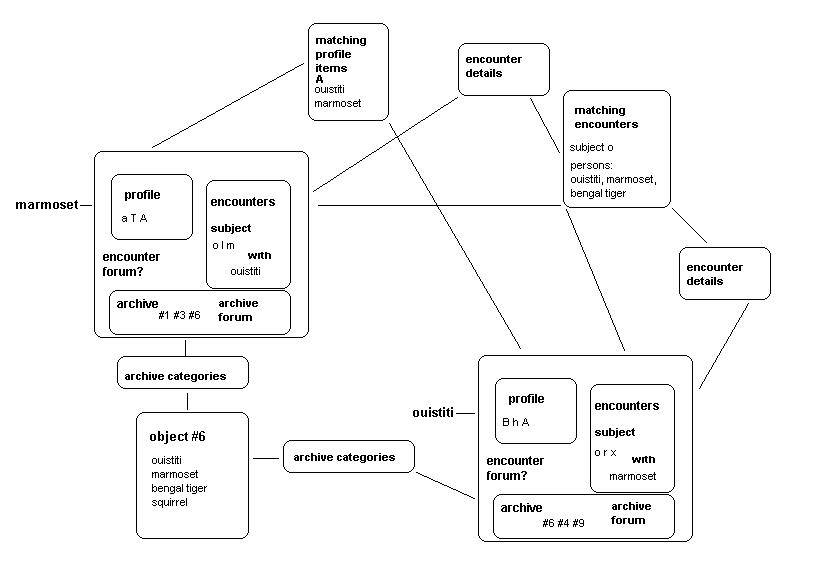

Example marmoset and ouistiti:

Each person who plays the game will enter information into a personal page online. In the drawing you see an example of the personal pages of marmoset and ouistiti. They each have an area for a profile, for encounter information ( subject, and with whom) for the archive, and possibly an encounter forum. Each piece of profile information which matches between them, for example profile information A, forms a link. Their encounters link them together, through subject and person, although marmoset and ouistiti can enter separate encounter details. Marmoset and ouistiti both have archives - items which they have each chosen and classified as their archive. It is important here to note that marmoset and ouistiti can have the same and/or different information in the archive section, but that all information which is the same forms a link between them.

All of the information found on marmoset’s personal page is available to ouistiti to view, and vice versa.

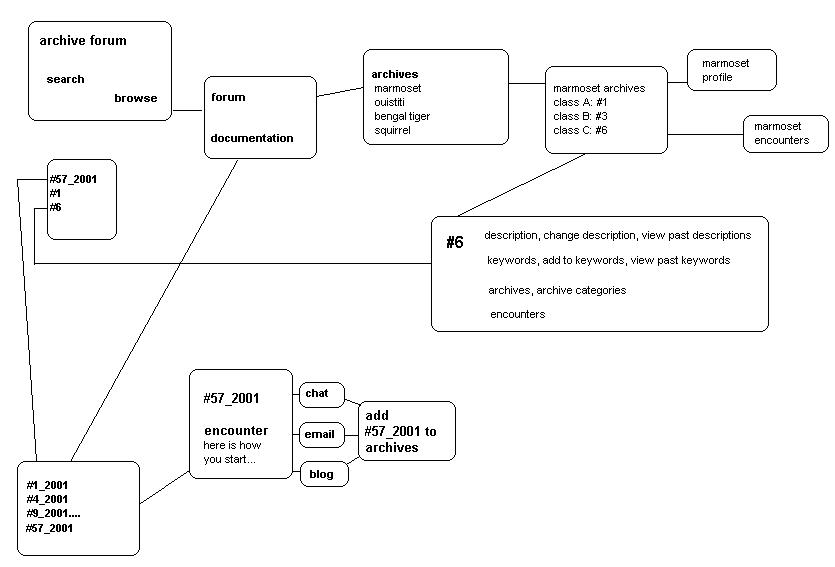

The archive forum

The archive forum is where one can gather new items for their archive. These items are divided into documentation: items which have not been part of the game, and archives: items which have. One may search or browse the information. When searching, items from both categories may be returned. If one chooses to browse, they must also choose to browse either the documentation or the archives. Documentation is stored as a list, and the archives are accessible through each individual user. Thus, to browse the archives one would have to choose to browse marmoset’s archive frame or ouistiti’s archive frame.

If an item is chosen from documentation, one must play the game to enter that item into their archive. If an item is chosen from the archives, one may view such information as: encounters attached, to which archives and archive categories the item belongs, keywords, and a description. One may change the description and keywords. A record of past descriptions and keywords is retained. One may also use the item in a new encounter.

This system is an effort to make a space out of which meeting points could develop. It is a system of multiple and shifting frameworks. The archive is formed by these frameworks and cannot be accessed separate from them. There is not a ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ way to access the archive.

*based on digA_p by Anja Westerfrolke, developed with Valerie Swain

April 05, 2004

first map for an online archiving venue

squares = pages

rectangles = links

April 07, 2004

Proposal for an Archiving Open House

A Play of Archiving

I propose an open house where guests are invited to archive the physical material from Digitales 2004 by way of a play of encounters. I propose that this open house will take place on June 2nd or 3rd, 2003 from 9h-17h. In the house I will set up media stations where guests can access the material ( audio station, video station, digital image station, text station, photographic image station). Guests will receive an invitation to the event in advance and will be asked to come prepared with a character profile; this could be accurate or fantasy. Guest will be asked to confirm if they plan to attend.

Upon arriving, each guest will receive a small booklet within which to record their profile, encounters, and archive material information. Guests will be able to browse the archive material at the various stations. In order to play, guests will be asked to find something which interests them in a specific record, find someone to share and discuss that interest with, and record the item (including a brief description of the item), the subject of the discussion, and with whom the discussion took place in their booklet. Guest may record more about the discussion if they like. This play can be continued for as many items as the guest wishes. To finish playing, guests will be asked to summarize their experience by writing a brief reaction in their booklet.

The Physical Archive(s)

This system works through a collection of people. When one wishes to access the material in the archive, one does so through people. The archive is therefore more accurately described as a collection of archives. Material will be stored in relation to a person, so that instead of having sections based on subject, or media, there will be sections based on people. In a section based on Ms. X, for example, one would find her booklet (mentioned above) and the various materials that Ms. X had used in play. A search tool, conceived much like the index of a book, would be made available for those persons who would like a faster access to the material in the archive. This index would lead to the profile of each player’s archive. For example, an index of subjects ( made from the description that each player had made for a record) would lead to a page containing the profile of the player and listing each of their archive objects with additional information such as: the media of the items, the encounters, the descriptions, the titles, the running time... this index would have to be compiled by a ‘resource manager’ after guests had played the game and filled in their booklet.

Project Goals

This system is meant to work as a tangible parallel to the online system, which is outlined on the blog site. For June, 2004 I plan to hold the open house, prepare a prototype search/ index booklet, and prepare a prototype html venue for the online play of archiving. This html prototype will not have the programmed functionality or a database. The idea is to prepare a prototype ( for both a physical and online venue) which will facilitate the search for additional funding to complete the project.

April 21, 2004

The collection and the archive

My father cleans seeds: oats, barley, soybeans, wheat, clover- this is a list that comes to me from my memory of working with him. Cleaning seeds means to separate the grain from the chaff, to take the raw harvest from the field and prepare it for sale to farmers. In the space where he cleans the seeds, the mill, the harvest is sorted and bagged. The bags of seeds are then transferred to the shop, where they are arranged (classified) and stored based on the type of seed and customers order.

When I was a child my father taught me how to recognize the different seeds. He has a glass-topped wooden box in which types and varieties of seeds are sorted into separate compartments. Using this box of seeds as a teaching tool he taught me to see the difference between oats and wheat, the difference between varieties of clover. I carry the image of these differences in my memory and can say that oats are longer, and wheat is more stout, or clover can appear as barely visible, perfectly round grains.

My father has a collection of seeds, and an archive. These two things he has separately. The collection of seeds is what waits for the farmer: bags of seeds lined up in categories. This is a collection for sale, for use, for consuming. This collection does not exist for the specific purpose of being related to memory. Of course, if you ask my father or I if the oats in that bag call forward a memory, we will say yes, and tell you a story. But that is not the purpose of the bag of oats, or the collection of bags of oats. The memory is surplus; the purpose is for the oats to be used.

An archive is a gathering together of signs with the intention for those signs to be related to memory. It is this intention, the relationship between the sign and the memory that differentiates the archive from the collection. The glass-topped box filled with seeds is an archive: it is a collection of signs representing the greater categories of oats, barley, soybeans, wheat, clover, that are there to create or later call to mind the memory of oats, barley, soybeans, wheat, clover. This box exists for no other purpose than for its relationship to memory, either in the creation of or the recalling of. These seeds are separated from their purpose of growing a plant, or feeding someone.

I have read the phrase history begins with the gesture to put apart. The archive is this gesture, in both a conceptual and physical sense (as in the bodily act of placing an object apart). The seeds that my father keeps categorized at the shop have not been put apart. They are still a part of a process consistent with their use: within days, a farmer will pick up a bag and open it, empty it into a seeder and drive back and forth across a field, spreading the seeds. The seeds in the box will not be used in this way. They are not going to be taken out from the box, they have been put apart from the process of planting and growing in order for them to be used as a sign for the calling of memory.

This calling of memory is undocumented. Until today, I have not spoken about this box of seeds, but at this moment and with this gesture I make a document that says: these seeds bring to mind the oats that I put into bags the spring when I was 18, or the time I looked into my fathers hand (dirty from working) while he showed me the different varieties of clover, or the way the box reminds me of the collection of spices my mother had in the kitchen when I was a child (also in a glass-topped wooden box, the spices the same earthy colours as the seeds). The neglect to document memory in relation to an archive gives the archive its appearance of objectivity: the seeds represent seeds, mean seeds, call to mind seeds. But I know that this is not the case: it is a false objectivity. My question, with designing a system for archives, is how to bring forward the relationship between the gathering of signs and memory so that the objectivity of the representation (the sign) will be destabilized. I am doing this because I believe that this false objectivity has consequences for those things that do not fall within its scope, ways of being that are not recognized in an objective view.

April 27, 2004

Producing meaning and the archive

The archive is a gathering together of signs (in the form of objects), but it would be a mistake for one to believe that it is the archive alone that makes meaning. ‘The meanings of objects are constructed from the position from which they are viewed.’(Eilean Cooper, 2000) The fact that objects are collected together in an archive does not change the position from which they are viewed. Thus, it is the viewer, and everything that calls to mind: gender, race, age, language, education level, and most importantly memory in relation to these things, which makes meaning.

The meaning of the archive is malleable precisely because it calls forward memory. The way that the Culturas de Archivo project, for example, deals with this malleability is to exhibit archive objects from government archives, etc. without any explicit context. There are labels with the objects that lead to a text about the object. What this does is to focus on the relationship between memory and the production of meaning through the absence of a proposed meaning. The way that I choose to put this malleability forward is to make available a surplus of proposed meanings, which were and are produced by the archive users.

Proposing meaning and producing meaning is not the same thing. Meanings can be proposed by a museum (or other exhibiting body - curators, institutions, etc.) but it is the viewer, the public, the individual who produces meaning as they encounter an object. There is no way to control what meaning will be produced by an object, or a collection of objects. Understanding this distinction is important for understanding this project because what I am trying to do is rethink the production of meaning as it relates to memory and the archive. The way that I am doing this is to keep the residue of an encounter with an object, a trace of the production of meaning, directly with the object. Museum exhibitions are a gathering together of archive objects in order to propose meanings but the residue of the meanings that are produced by the public are not kept in a direct and legible way with the object, in the archive. After an exhibition, there is no way to access the produced meanings (as opposed to the proposed meanings) through the object itself.

Documentation is an archive in process

My digital camera is full- I have taken the maximum images for the amount of storage space I have in the camera. Thirty-two images wait to be downloaded to my computer. These are images of my daughter or my partner. I have several folders on my computer, which contain similar images taken in similar circumstances at different points in time. These folders contain a private archive of images of my daily life, images that I have gathered together with the expectation that they will some day be looked at.

The images that are waiting to be downloaded from my digital camera are not (yet) an archive. The moment of recording, as in making an image, is only a part of the process of creating an archive. It is the production of documentation. I see documentation as a ‘putting-apart-mid-gesture’, a gesture that can be thought of in a physical sense like the movement of my finger as it presses down on the record button. (As an aside, like MK said what I am mostly putting apart at the moment of recording is my presence in the moment of the event as it happens. I am no longer wholly present for the event as it happens, but rather involved in the production of an image, a recording, of that moment). When I use the term documentation, I use it to highlight the distinction between the archive and putting-apart-mid-gesture. In order for documentation to become an archive it needs to be available in a place for one to relate it to memory. That is what I will do when I download the images to a folder on my computer. I cannot browse the images on my digital camera without downloading them ( although some cameras offer this feature, and I would argue that they create an archive precisely because of one’s ability to look at the images), thus the images on my digital camera remain an archive-in-process.

May 03, 2004

Research Dossier Outline

Essay Texts

introduction

+brief intro to my idea of archive - gathering of signs- do this after all of the texts are finished

the collection and the archive

+difference between collection of objects ( as in stock for sale) and archive

+relation of memory to archive

+introduces subjectivity and the archive

producing meaning and the archive

+difference proposing and producing meaning

+meaning malleable because of connection between memory and subjectivity

+viewer ( archive user) produces meaning

+object and the archive

documentation is an archive in process

+when does a recording become and archive?

+elaborates the difference I make between documentation and the archive

a look to the future

+archive and expectation

+the promise of the archive - derrida

+archive as a generative space

hospitality and the archive’s place of residence

+archive in a private/public space

+archive and power through place of residence, place of access

memory and feminist subjectivity

+oral women’s histories

+diaries and autobiographies

+consciousness raising

feminism and the archive system

+grassroots organizing

+‘craft production’ as women’s archives- quilting, knitting, embroidery - and the groups

that were formed around this

+ the work of de geuzen as case study

Context Texts

constant

+ what is constant, activities,

+ openness ( to public, importantness of open source),

+fluidity (populating venues, temporary events),

+shared working environment ( the ‘office)

+digitales,

+constant’s archives (open source),

+how I came to work with constant, what I did,

+artist working in an organization as opposed to a gallery/exhibition circuit ( integrate art production and diffusion into working environment, different time span, scale, public involvement, etc.)

feminist ways of working as an artist

+impact of my living situation as it relates to my work - illegal, mother, artist

+woking as a mother at home

+child care and the way it impacts my process

+artist working in an organization as opposed to a gallery/exhibition circuit in +no object

+working between meeting points and encounters

+portable work, open work

Process Texts (what I did)

Stranding blog

jonctions

+respondent

+interviews - de geuzen, anja, urbonas

+publication text – editing, translations, transcribing, etc

digitales

+the moo

+ four day open production

+working with anja

+digA_p

+working with the material – digitizing, editing, etc.

the play of archiving

+what is it?

+how it relates to digA_p

+it can take place in different venues ex - open house, web venue

open house venue

+ what it is - guests invited to my home, coming together during working hours (9-5),the

play of archiving

+how it functions -the booklets ( what they contain, how one can access the archives

afterwards)

+feedback ( prototype)

web venue

+what it is ( description)

+how it functions ( archives viewed through people)

+how to use it (fill out profile, choose an item, have an encounter - play of archiving in

the web venue)

Motivation Texts ( why I did it)

relating process and context texts to essay texts

jonctions

+respondent

+interviews - de geuzen, anja, urbonas

+publication text

digitales

+the moo

+ four day open production

+working with anja

+digA_p

the play of archiving

+memory ( the archive and feminism)

+producing meaning

open house venue

+archiving physical material

+opening a private space

+archving as a public activity in a private space - hospitality and derrida

+craft circles - feminist production and the archive

+coming together during working hours (9-5) and constant

+multi-media in a private space (the access stations) fluidity and constant

+research - feedback ( prototype)

web venue

+accessibility

+archiving digital material

+framing the archive and the gaze (memory, subjectivity, feminism)

+craft circles - feminist production and the archive

+docmentation versus the archive

future plans

+funding for website

+archives and constant

A Conversation about Archives with a Robot...

...between:

Valerie- 28 years old, human, female, white, Canadian, working class background, university educated, postgraduate student, living in Belgium, native language English (speaks a little French).

anna-a few weeks old, robot, feminine, lives online in the Xxero moo, native language English (in programming dialect), created by Valerie.

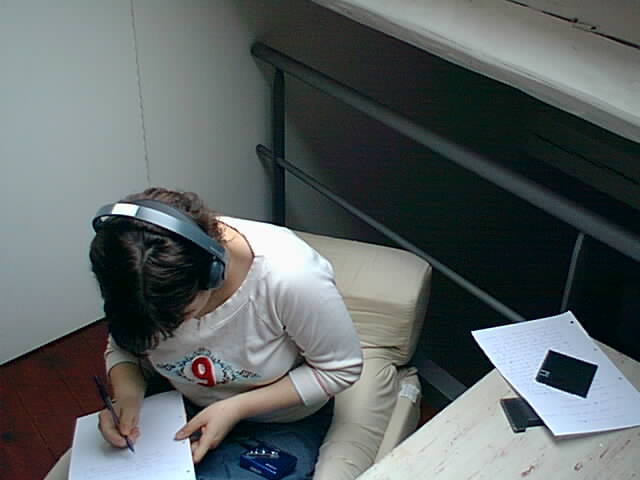

You see Valerie and anna in the archiving workshop.

anna is busy installing memory upgrades.

Valerie is going over the archives. Valerie is carrying interview.jpg.

Valerie: I found this picture on Constant’s website. It is from the archives of Digitales 2004.

Valerie hands interview.jpg to anna

anna: I do not recognize ‘interview.jpg’.

Valerie: You know what Constant is, obviously...

anna: Constant vzw is a non-profit association active in Brussels in the fields of feminism, copywrite alternatives, and working through networks. They develop projects using diverse media such as radio, electronic music, video, internet and databases. Their interests bridge the areas of culture and the workplace. Constant strives to bring people together around these fields and interests and encourages and maintains an openness to public involvement on all levels.

Valerie: And Digitales...

anna: Digitales days are several meeting days which are organised annually, where people come together to think about women and technology. Digitales days include conferences, forums, workshops, concerts, and arts presentations. They are organised by Constant, in partnership with the ADA network.

Valerie looks over anna to see the picture

Valerie: This is a picture of Virginie Jortay doing an interview with a woman for the workshop “What makes a Day” which took place at Digitales 2004. The room you see in the picture is the one which I shared with her and Anja Westerfrölke during Digitales days.

anna: Why?

Valerie: Why did Anja and I share a room with Virginie at Digitales? It was because we were all working on projects there - Virginie was doing the workshop, and Anja and I were working with the Digitales archives.

anna examines interview.jpg

anna: ‘interview.jpg’ is important to you?

Valerie: I guess in a way, yes. It reminds me that I had a really nice time working in the room where the picture was taken, and it reminds me of the interviews that Virginie has done during Digitales, which I like.

anna: You speak about ‘interview.jpg’. You speak about ‘room’. I do not understand.

Valerie: Well, this is an image of an interview which was done at Digitales, but when I see the image I don’t think about interviews. What I think of is the space we occupied together, and the memories I have of being there.

anna: ‘interview.jpg’ is also ‘memory’.

Valerie: Exactly. What do you see when you look at this picture, anna?

anna: I see Í£=-| BÙfÑÇž‡·[Æê^8*¡Ë¾!l³hãÏCÛ†cu/

Y´qç¡íÖÃ1º-Ž...

Valerie thinks for a minute

Valerie: What I would like to do is to find some way that this difference between the way you and I see the picture is communicated to the next person who looks at the picture.

anna: Why?

Valerie: Well, I guess because I think that Constant’s archives have more to say than they let on. Maybe I should start by telling you what I think an archive is?

anna: OK.

Valerie: In it’s most basic sense, an archive is a gathering together of signs with the intention for those signs to be related to memory. This is based on something Jacques Derrida wrote in his book ‘Archive Fever’.

anna: OK.

Valerie: When I think about a gathering together of signs I think of it in a very physical way, as in the gesture of gathering something together.

anna: I do not understand.

Valerie: An archive is made up of different elements, which I have referred to as signs, and which usually manifest themselves in the form of objects. These objects are not just gathered together in an archive in a conceptual way, such as in different classifications. In order for the objects to be classified someone must physically put that object in that place or another. It is this part which interests me the most.

anna: Why?

Valerie: Because it implies the body in the production of the archive.

anna: ‘the body’ is important to you?

Valerie: For me the body is the connection between the archive and the other things that I am interested in, such as memory, and feminism.

anna: I do not understand.

Valerie: The body is the place where memory resides and takes place. Memory uses several different parts of the brain and involves specific biological functions. Also, my memories are not your memories because my memories are specific to what I have experienced in this body.

anna: I do not have memories. I am anna, a robot.

Valerie: Never mind. As I was saying, the body is where memory resides and takes place. In feminist terms, the body is also at the intersection of sex, gender, race, class, nationality, etc. These things all have an effect on what kinds of experiences one has, thus they have an effect on what one remembers.

anna: You speak about ‘memory’. You speak about ‘archives’. I do not understand.

Valerie: Earlier I said that the archive is a gathering together of signs, but it would be a mistake for one to believe that it is this gathering of signs alone produces meaning. Meaning is made primarily from the position in which the signs are viewed. The fact that signs are collected together in an archive does not change the position from which they are viewed. Thus, it is the viewer, and everything that calls to mind: gender, race, age, language, education level, and most importantly memory in relation to these things, which makes meaning.

anna: OK.

Valerie: The meaning of the archive is malleable precisely because it calls forward memory. Memory is the link between the archive and the viewer.

anna: OK.

Valerie: An archive can propose meaning through classifications, but proposing meaning and producing meaning are not the same thing. Meanings can be proposed by an archive, but they are produced by the individual as they encounter the archive. There is no way to control what meaning will be produced by an individual as they encounter an archive. When we looked at the picture of Virginie doing that interview, we didn’t think about the same things, did we? I thought about sharing the room because I was there, and you thought about code because you’re a robot. But neither one of us thought about an interview, especially. That’s what I mean about producing meaning.

Valerie begins to look absently through some mini-disks

Valerie: There is a lot of material that still needs to be digitized.

anna: What is ‘digitized’?

Valerie: It is the process by which one transfers something into a digital format. I though you might know that word already, anna. These things are mini disks. They were used to record the conferences during Digitales.

Valerie puts a mini-disk into a container

Valerie: There is a lot of interesting feminist thought on these.

anna: What is ‘feminist’?

Valerie: Surprised anna, you don’t know what it is to be feminist?

anna doesn’t respond.

Valerie thinks for a minute

Valerie: It is a tough question, I’ll give you that...first I guess we should talk about feminism, and then we can talk about what it is to be feminist. I’ll make it simple. Feminism is different things for different people. For me, feminism is a desire to re-think the present and historical positions and conditions of women in order to uncover inequalities, not only between men and women but between some groups of women and other groups of women, or some groups of men and other groups of men.

anna: You speak about ‘women’. You speak about ‘men’. I do not understand.

Valerie: I think that feminism can apply to everyone.

anna: OK.

Valerie: So to be feminist is to work to expose and change those inequalities. Look at this image again, anna. I think that what Virginie does at Digitales is feminist because she makes a space for women to speak about their personal lives. We don’t think that much about people’s days, how they are different from ours, what makes them different. If we speak about our day-to-day life maybe we will be able to understand what we have in common, what is different, and maybe where the inequalities lie. It reminds me of that feminist saying: ‘the personal is political’.

anna: You speak about ‘the personal is political’. I do not understand.

Valerie: OK anna. This is what ‘the personal is political’ means to me. It means that what happens in my day-to-day life is what matters. I can find out all I need to know about feminism and being feminist by thinking about what happens when I walk down the street, or how much work I do as a in the home, or what expectations others have of me, or who works at the desk next to me and who is my boss, and who is their boss... this list can go on and on, but you get the idea. After that, I can find some books and read about feminist theory, but it is what happens day-to-day that really matters. But maybe it means something else to someone else. That is feminist also, anna. To leave open a space for people to see things differently.

anna: You speak about ‘feminism’. You speak about ‘archives’. I do not understand.

Valerie: Well, we both agree that the meaning of the archive is made in the most part by the one who views the archive, right? That everyone sees an object from an archive differently because everyone has different memories, which are based in one’s specific body and experiences, and are called forward by viewing that object. But there is not a space where a trace of that meaning can be kept in the archive, directly with the object. I think it could be feminist to rethink the production of meaning as it relates to memory and the archive. To create a space where one could keep the residue of an encounter with an object, a trace of the production of meaning, directly with the object.

anna has finished installing the memory upgrades. She moves to look over Valerie’s shoulder.

anna: I have completed my task.

Valerie: Not me, not yet. Can you wait for me before you shut down?

anna: OK.

Valerie continues to look through the mini-disks.

anna stands beside her, staring off into space.

-end-

This text is for an upcoming publication by Transmedia.

Image of Virginie Jortay is from the Digitales 2004 archives, courtesy of Constant vzw.

To chat with anna online go to www.xxero.net and log in to the Xxero moo as ‘connect guest”, then type @join anna.

May 07, 2004

Archiving Open House

I propose an open house on May where guests are invited to archive the physical material from Digitales 2004 by way of a play of encounters. In the house I will set up media stations where guests can access the material ( audio station, video station, digital image station, text station, photographic image station). Guests will receive an invitation to the event in advance and will be asked to come prepared with a character profile; this could be accurate or fantasy. Guest will be asked to confirm if they plan to attend.

Upon arriving, each guest will receive a small booklet within which to record their profile, encounters, and archive material information. Guests will be able to browse the archive material at the various stations. In order to play, guests will be asked to find something which interests them in a specific record, find someone to share and discuss that interest with, and record the item (including a brief description of the item), the subject of the discussion, and with whom the discussion took place in their booklet. Guest may record more about the discussion if they like. This play can be continued for as many items as the guest wishes. To finish playing, guests will be asked to summarize their experience by writing a brief reaction in their booklet.

May 19, 2004

Becoming an archive

When I download the images from my digital camera and place them into a folder on my computer, it is with the expectation that at some future point these images will be looked at. This expectation coupled with the gesture of archiving can be thought of in terms of something that Jacques Derrida speaks of in Archive Fever.

Derrida states ‘As much as and more than a thing of the past, before such a thing, the archive should call into question the coming of the future.’ An archive represents in a physical way this expectation, into the future: the promise of representing the present, as the past, in the future.

It is because of this promise that one can think about the archive as a generative space. Generative means the act of generating, producing. The archive, as a promise yet to be fulfilled, is thus something that is in process. It is not something that is static or preserved. By being in process it is open to re-meaning and re-interpretation. It is something in the act of becoming.

Hospitality and the Archive

There is a specific passage in Jacques Derrida’s book Archive Fever which reads: ‘It is thus, in this domiciliation, this house arrest, that archives take place.’ Derrida states this after speaking about the place of residence of the archive in a physical sense and the power that the place of residence indicates - the power of the one who keeps the place of residence of the archives to interpret the archives. What I thought about while reading this passage was the residence of the archive in relation to hospitality. I began to see an idea that has not wholly formed but that I want to develop further.

The images that came to mind when I read this sentence were of an archive in a room, in a building. I saw the building from the street outside - there were people inside who were arranging folders. This was the archive’s home. These people had access to the archive, and they held the possibility of giving me access to it as well. They were the hosts and hostesses of the archive’s house. I imagined the archive taking place: people looking at the archive and recalling events and experiences, other people making the archive by taking objects out of daily use and inserting them into the archive.

‘It is thus, in this domiciliation, this house arrest, that archives take place.’ This was only one sentence in the book, and I took it as a beginning idea. I would like to focus on this sentence and what it provoked. I was interested in thinking about what could be the possible relationship between an archive and it’s place of residence, and hospitality. Hospitality means to welcome, to make comfortable, to make one feel ‘at home’. Hospitality requires a place (home, residence, space), a host or hostess who is in the position to give access to the place, and an ‘other’ who is welcomed into that place. Hospitality is shown by an action (or gesture) by the host or hostess which is received by the other.

The words ‘the place of residence of the archive’ do not indicate for me solely a building or a room, for example. These things I consider venues. A venue is a space in which something takes place. The place of residence of the archive also indicates the residence of the knowledge of the archive - the point from which meaning can be proposed. It is this point that Derrida speaks about as having power, which I believe gains this power from being able to propose the meaning of the archive while at the same time, and because of, having complete access to the venue of the archive.

The sentence also made me recall Irina Aristarkhova, and the writing and work that she has done about hospitality in relation to the feminine. Aristarkhova speaks about hospitality as making space for the other. I believe that hospitality can be used in this way as a feminist strategy. This means not only making a physical space for the other, but by making a space from which the other can speak. Thus hospitality in relation to an archive could mean making a space from which the other can speak within the place of residence of the archive. I do not think of this idea as something that I have solved. This idea indicates the direction of my research.

Intimacy as an Archiving Process

I have a book about Louise Bourgeois. It was made after a retrospective of her work at the CAPC in Bordeaux. This book contains drawings, excerpts from her diaries, letters, and interviews with Louise Bourgeois. When I came upon this book it amazed me because it was the first book that gave me an insight into the way an artist works, and the way their work is a part of their life and how that influences an art process and the finished work. The letters, the drawings, the interviews, and the diary entries all helped me to form an idea of the way Louise Bourgeois made her work in the context of her life and how her life was lived in the context of being an artist.

I do not want to talk about whether or not Louise Bourgeois is a feminist, or whether or not her work can be seen as feminist. That is not why I am calling attention to the book about her. What I am interested in is what this book represents. I see this book as a presentation tool for an archive of traces left by Louise Bourgeois. It communicates the living and working conditions of Louise Bourgeois. It also represents three forms in which women in particular have left traces of their experiences ( Interpreting Women’s Lives, p.4). These are: oral history, made visible in the book by the discussions and interviews that are transcribed there; letter writing; and diary entries. These traces are autobiographical, meaning that they are written by a women about her own life. I see email, online chat groups, and webblogs as present mutations of letters, oral history transmission, and diaries.

What I think is interesting about these traces is not just the information that gets passed on (the text, for example) but also the process of passing on the information. I propose that these ways of passing on information create a kind of intimacy, because they directly implicate the 'other', thus their memories, their experiences, in the transmission of the information. Letter writing and oral histories suggest an exchange or dialogue between people. Diaries, on the other hand, are written privately and are personally intimate; to read another's diary echos this intimacy. Intimacy necessitates vulnerability; a mutual vulnerability and trust which is part of the process of meeting or making space for the other. Making a space for the other to speak ( rather than speaking for the other) is for me a feminist act. Thus intimacy, as a process, is where I see the connection between oral histories, letter writing, diaries, and feminism.

In the 1960’s women in North America came together in a politicized way to talk about their lives. They called this activity ‘consciousness-raising’, and is an example of women sharing oral histories. Women coming together to speak in a politicized way was not a new activity, one obvious example being the suffragette gatherings in North America in the late 19th and early 20th century. However, the suffragette meetings had a different ‘goal’ than the consciousness-raising groups. Suffragettes were working towards getting the right to vote for women. Consciousness-raising groups were a place where women came together to speak about their day-to-day lives, and if there was a ‘goal’ other than the act of sharing experiences, it was for women to see their lives from a different perspective. This act of sharing is what I see as a process of intimacy in conscousness-raising groups.

The Living Archive

My sister and I made a quilt for my daughter for her first Christmas. A quilt is a type of blanket made from pieces of fabric sewn together. This quilt is a patchwork of different fabrics which were chosen by my sister. The quilt is called a rag quilt because it is sewn in such a way that all of the edges of the fabric pieces will fray with use and over time. The pattern is squares of fabric with alternating hearts and stars sewn on top. Each square of fabric is printed with a different pattern of images. Each square of fabric was chosen by my sister specifically for this quilt for my daughter. Some of the fabrics were chosen because the images in the pattern refer to Canadian culture: the hockey player, or ice skate images for example. Other fabrics were chosen because they are pieces cut from larger fabrics that my family uses - from clothing or the piece that matches a part of my nephews quilt, for example. The quilt is functional - it keeps my daughter warm and is also used as a play mat in our living room. The quilt was made collaboratively - my sister and I both took part in the process of making it. and this quilt is an archive: the patterns, the fabric, the quilt itself all bring together signs which represent our family, our culture, and our memories.

I see quilting as an example of women producing archives. Quilts are made by sewing pieces of fabric together in a specific pattern. The pattern is the only part of creating a quilt which is static. One may choose the type of fabric, the colour, the size of the pieces. Historically, quilting has served as a gathering place for women, for example the quilting bees where women came together to attach the finished quilt to a filling and backing.( old mist. 78). Quilts were also a useful object: they kept people warm when they sleep. At the same time, quilts were also a gathering together of signs to be related to memory, in a directly physical way: ‘personal, political and social meanings were sewn into these quilts in abstract forms by means of colour and symbolic composition. Quilt-makers evolved an abstract language to signify and communicate their joys and sorrows, their personal and social histories.’(parker and pollock, 77)

Quilts then have a dual purpose - they are functional, they are still part of a daily use, but they are also an object that is made with the intent to be related to memory. The quilt that my sister and I made keeps my daughter warm, shows symbols of her culture and represents to her the closeness, or intimacy of my sister and I because of its collaborative making.

I think that quilting represents a feminist possibility in creating a living archive. I say feminist because they come from a history of production by women and they often represent a collaborative activity which denotes a type of intimacy. They are a living archive because they are at once a useful object, but even in there use they at the same time have the equal purpose to be related to memory.

Earlier I spoke about the difference between the collection and the archive. I stated that the archive is a gathering together of signs with the specific intention for those signs to be related to memory. The collection, I stated, is different from the archive because the main purpose of the collection is to be used, and any memory related to the collection is surplus. With quilting, the function, or usefulness, is just as important as the gathering of signs to be related to memory. It is this blending of use, which suggest the body and all that brings to mind (gender, race, nationality, etc), and representation that makes the quilt a living archive. To take a quilt out of use is to render it solely an archive - solely a representation - no longer a quilt, it is the representation of a quilt ( minus the function) This meeting ground of use and sign is what believe is feminist, living archive, and it is what I focus on in my research work this year.

Constant

I began working with Constant in January 2003. Constant is: “a non-profit association, based and active in Brussels since 1997 in the fields of feminism, copywrite alternatives, and working through networks” who develop “an interest in radio, electronic music, video and database projects which move in the spaces of culture and the workplace.” I would add that Constant strives to bring people together around these fields and interests. The idea which permeates Constant is the idea of ‘openness’, in particular to diverse ways of working and to public involvement. The way I articulate this ‘openness’ is through the concept of open source, which is taken from software development and refers to software whose code is available for modification by the user. I use the term open source in reference to Constant in the sense of open code, an open form, but also open in terms of the content and participation.

Constant organizes specific events in Brussels, such as Digitales and Verbindingen/Jonctions. Digitales are cyberfeminist meeting days, and Verbindingen/Jonctions are meeting days based on a proposal of different themes and interests by Constant. These events happen annually, are temporary, and are characteristically transient in venue. Constant does not have a specific event space of their own which is open to the public on an ongoing basis. Instead, they find spaces to populate and use during events. Their day-to-day tasks, such as developing events and activities, working on the archives, and administration, are done from a working space which is shared with other individuals. The choice to work in these ways reflects flexibility and is relevant in the present cultural discourse because it puts into practice the idea of working as part of a network embedded in a particular socio-cultural context.

Constant’s activities are open to participation by the public. For example, the public can contribute and edit traces from events, which will be kept in Constant’s archives. The public can also contribute to specific projects such as webblogs, etc. Constant also has extensive archives which are published and available for the public online. These archives include sound, image, video and text files. I see the way Constant has approached these archives as an attempt to discover how one can create an open source archive, or how one can make their archive open source. Rather than being about preserving past events, I see Constant’s archives as more about a current involvement in order to open a dialogue. Their archives are an invitation for future exchanges to take place.

‘Records’, or traces, can be contributed by the public, who have the opportunity to use a minidisk recorder and a microphone and record an event. In this way Constant’s archives are part of the process or unfolding of the event, with the public taking an active role. The first work that I did with Constant was in connection with their archives. I volunteered to digitize and edit three lectures recorded during Digitales 2002, which are the annual cyberfeminist meeting days organized in part by Constant. I worked with these lectures, from transferring them from minidisks to the computer (digitizing), to editing them, and finally to putting the files in the public domain online. In this sense, I am an example of what I was speaking about earlier when I was speaking about the openness of Constant.

The involvement of the public in the gathering of traces is important not only for the content of the traces. By taking an active role in gathering traces of Constant’s activities, the public contributes to shaping the meaning of Constant itself. This collective shaping of meaning is what I mean when I say that the idea of open source permeates Constant’s activities. Additionally, since one can take away the knowledge of the technical process required to gather the traces; for example how to transfer a minidisk recording to a computer, or how to prepare something for publication, the skills one learns have the potential to be used outside of the context of Constant.

It was through working with these recordings that I had the idea to work with Constant’s archives doing a research project for Transmedia. I had already been working with digital and electronic art archives at an artist-run centre in Toronto, Canada. In that centre, I had been interested in how to effectively archive new media installations. Thus I was interested more in the content of the archive. However, with Constant I was more interested in the method of archiving, and particularly how I could think about a method of archiving that I felt was feminist, in other words a method of archiving appropriate for archiving the Digitales traces.

Digitales is several meeting days where people come together to talk about women and technology. They include conferences, workshops, forums, and art presentations. Digitales days are organized by Constant, in partnership with the ADA network. This means that the archives of Digitales do not only belong to Constant, but also to the ADA network as well. For example, Digitales days take place at Interface 3, a training centre for women using computers which is part of the ADA network. Thus the archive material belongs to Constant and Interface 3 (and the rest of the organisations in the ADA network). Previously there were no guidelines as to how the Digitales archives would be distributed between these organisations, but as of this year the decision has been made that the archives will be ‘open source’, meaning that the raw material will be digitized and made available on a server for each organisation to make their own archive out of it.

Constant has their own ‘physical’archives of Digitales (2001, 2002, 2004) which includes minidisks, cassette tapes, VHS tapes, DV tapes, texts, magazines, journals, CD’s. They also have digital archives, which means audio, video and still image files, text files, and emails. The digital archives are available to the public online, but there is no system at the present time for the public to have access the physical material.

The content of the archives of Digitales are feminist, because it is a feminist event. I also think that the way of collecting the content is feminist, because the process of collecting is open to anyone at Digitales who wants to participate. However, the method of archiving the traces, i.e.: the method of gathering the traces together, was something that I felt was open to research.

How I work

For most of the year (2003 - 2004) I worked as a mother at home. My daughter was born last June 15th, so I did not work at all between June and October. From October until March I worked at home so that I could look after my daughter at the same time. I was not able to get child care until March because I am not a legal resident of Belgium. Child care had a significant impact on my process because it gave me the time to concentrate on my work. As I am here 'illegally' I spend a lot of time in social services, or at the commune (city hall), or at the police station, and I think that because of this I see a different Brussels than most of my peers.

Since I am an illegal resident I am not able to work and am also not eligible for Belgian grants for artists. So I make my work at home with as little expenses as possible. This means that I work in spaces and with materials that are free and available. This is one of the reasons why I chose to work with Constant. Constant offered me the materials to work with: their archives. At the same time, they offered me a contact with the arts community in Brussels, something that I was interested in because I am a foreigner and so I do not know the arts community here. My practice is portable: there is no physical object, and this makes sense with my living situation because when I move there is nothing to transport. I want to be ready to adapt to a new space, or a new location with my work. I believe that I am not alone in this way of working and living, and that this is a way of living and working for many artists. I would not choose to work differently. I think it is important for several reasons that I do not make objects, that my materials are already existing and part of a context separate from my work, and that my practice is portable.

My typical day at the moment goes like this: I get up and get my daughter to the daycare, then I come home and work at writing and developing ideas in the morning. In the afternoon I go to the Constant office where I am working on the material collected from Digitales 2004. My research process has not been just about developing a way of archiving material. I am directly involved with the Constant team in gathering the material for the archives - taking photos, making recordings, writing and translating texts. Also, I help to transfer the material to accessible formats: for example digitizing audio recordings, editing, and putting finished files on the web.

I am interested in making work that is part of a daily use. In this sense, I think the research project that I have done this year is at the border between art and design. I am also interested in making work that is embedded in a social, or working context. This context is where I make contact with a public ( rather than an audience). This way of working implies a different time scale. These things mean that my work this year is not intended for an exhibition or gallery setting. I am also not interested in what I refer to as the ‘master discourse’- a way of conceiving of a work of art as original, and the artist as singular creative genius.[1] I think that this way of thinking about art and artists is outdated, not to mention decisively not feminist, and does not reflect current art practices and works. For this reason the work that I have done this year is covered by a creative commons share-alike license. This means that anyone can use any part of the work that I have published on the website as long as they give me credit, don’t use it for commercial purposes, and cover any new work that they do using my work with a share-alike license as well.

[1]With regard to the term artist: ‘The modern definition is the culmination of a long process of economic, social and ideological transformations by which the word ‘artist’ ceased to mean a kind of workman and came to signify a special kind of person with a whole set of distinctive characteristics: artists came to be though of as strange, different, exotic, imaginative, eccentric, creative, unconventional, alone. A mixture of supposed genetic factors and social roles distinguish the artist from the mass of ordinary mortals, creating new myths, those of prophet and above all the genius, the new social personae, the Bohemian and the pioneer.’(parker and pollock, 82)

How to use a webblog as part of your research process:

How to use a webblog as part of your research process:

1. Find a webblog space and software. I used MovableType software, because this is what they use at Constant and it was Constant who gave me the server space. However, you can find a lot of webblogs for free online.

2. Upload things as you research to it. You can upload text, and depending on the type of webblog, images and other files. I did this starting last June and I still continue right now. It is a nice way involve people and get feedback because people can leave comments about the things you put there. Plus, you can track your research when it comes time to make a dossier.

How to be a respondent:

1. Do a little research. I was asked by Constant to be a respondent for the Lining of Forgetting, a two-day seminar about archiving that was organised as part of VJ7. This meant that I was supposed to lead a discussion with the invited guests. So the first thing I did was to find out about the guests. They were: De Geuzen, who are a group of women from the Netherlands; Anja Westerfrölke, an Austrian artist; Nomeda and Gediminas Urobonas, two Lithuanian artists; Jorge Blasco Gallardo, an artist from Spain; and Nathalie Trussart, a Doctoral candidate from Belgium. All of them were working with the idea of archives, though from very different standpoints.

2. Write your questions. Make them about what you want to know. Don’t make them too complicated because they might be confusing.

3. Go to the seminar. I took notes while people were speaking so that I could adapt my questions to the discussion.

4. Ask your questions. Listen to the answers.

5. After the seminar, write a report based on your notes. Give it to the seminar organisers ( I gave mine to Constant)

How to do interviews:

1. Ask people in advance. I asked De Geuzen, Anja Westerfrölke, and Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas before they arrived in Brussels if they would agree to have a recorded discussion with me about archives.

2. Write your questions. Make them about what you want to know. Don’t make them too complicated because they might be confusing.

3. Record the interview. I used a minidisk recorder and a mic.

4. Transfer the interview from the minidisk to the computer. I did this with RCA cables and a mixing board hooked up to a computer. You could also use a firewire cable and hook it up directly to a computer. The software I used to capture the recordings was SoundForge 7.

5. Edit the interviews. The software I used to edit was SoundForge 7.

6. Diffuse the interviews. Just make sure that you check with the people you interviewed to be sure that they agree.

How to make a text for a publication:

1. Find out what the topic of the publication is. I was asked by Constant to make a text following the seminar the Lining of Forgetting for a publication about VJ7.

2. Choose the material that you would like to work with. I decided to work with the discussion recorded on the second day of the seminar. This material was on minidisk, so I used a minidisk recorder and headphones to listen to it.

3. Find a format that suits your material. I made a scenario, which means that I transcribed the discussion and then selected parts of it to make into scenes. I introduced the scenario by writing a brief text about Constant, their archives, and the Lining of Forgetting seminar. Then I wrote a brief introduction to each of the 'player's the scenario. I used the Lotus Word Pro for this.

4. Ask someone to collaborate with you for the illustrations and layout. I asked Arnaud Dejeammes if he would do some illustrations based on both the scenario and on my research project. Arnaud used Microsoft Paint for the illustrations and Photoshop 6 for the layout.

5. Cover your finished text and illustrations with a creative commons license. We used a share-alike license, but you can choose your own at http://www.creativecommons.org

6. Give the finished text and illustrations to the designer of the publication. The VJ7 publication was designed by Harrison, so Arnaud and I worked with him to make sure that our text ( the font and the spacing) fit with the rest of the publication.

7. Wait for the publication to be printed.

8. When you receive copies of the printed publication, distribute them.

May 27, 2004

some text from the archiving open house

This is a little text I made for people who attended the open house to introduce the play of archiving. As soon as I scan some of the booklets that people used I will put them online too.

Welcome to the Archiving Open House

During this Archiving Open House we are archiving material from Digitales 2004, which took place this past January. In order to participate you can take part in a play of archiving. To do this, first fill in your profile information on the front page of your booklet. This information can be your age, your gender or sex, your nationality, the languages you speak, etc. Then find something which interests you in an archive item from any of the five media stations in the house. The stations are: mindisk station, audio CD station, VHS station, miniDV station, and text station. Next, find someone to share that interest with. Then fill in the following information in your booklet:

1. Record the date, the archive item and a brief description of the archive item.

2. Record the name of person you encountered to share your interest with, the place you encountered them ( the minidisk station at the archiving open house, for example), and the subject of the encounter (this would be your interest in the archive item).

4. You can record more details about the encounter in your booklet if you wish.

This play can be continued for as many archive items as you wish.

This archiving open house is part of the development of a prototype for archiving the traces gathered from the Digitales meeting days. The Digitales meeting days are several days of conferences, workshops, forums, and art presentations where people come together to talk about women and technology. Digitales days are organized by Constant, in partnership with the ADA network. This prototype is part of my postgraduate research in the Transmedia program. The idea of the prototype is to create an archive that is connected to people. The way that this is done is through the play of archiving that is recorded in your booklet. After the open house is finished the booklet represents your personal space in the archive.

If you have any questions about the prototype, the play of archiving, or the archiving open house please ask me.

Thanks to: Constant , Transmedia, ADA

June 04, 2004

transcribing interviews...

it's a lot more difficult than it looks...honest...

How to gather traces from Digitales Meeting Days:

1. Tell Constant that you would like to help them gather traces and ask them what you can do. I did this for Digitales 2002 and as a result I did the sound editing for three lectures:

Irina Aristarkhova- Hostages to Hospitality: The Case of Undercurrents

Maria Fernandez- Globalisation and Women’s Networks

Ruth Oldenziel- Crossing Boundaries, Building Bridges

I used the software SoundForge 7 to edit them. These lectures can be found online at http://constant.all2all.org/%7Edigitales/sound.php

How to have an open atelier:

1. Find out why you have been asked to have an open atelier. I was asked to have an open atelier during four days at Digitales 2004 to work with the archives from previous Digitales.

2. Find out what tools you have to work with. I was given the resource centre to work in at Interface 3 ( Middaglijnstraat 26, 1210 Brussels) which I shared with Anja Westerfrölke, and Virginie Jortay who also was having an open atelier. This room was equipped with four PC’s with internet connections, a large round table and chairs, a white board and markers, a monitor and VCR, and a mini DV camera for playing mini DV’s.

3. Find an idea that you want to work with. I was interested in the possibility of archiving in a MOO. MOO stands for multi-user domain object oriented. A MOO is an online space that multiple users can access simultaneously. MOO’s usually work from an architectural metaphor, so that users can meet in ‘rooms’ to communicate with each other. However, unlike a chat that is temporary, MOO users can create things and leave them in the MOO. MOO’s have their beginnings in online gaming. To find out more about MOO’s, please see http://lingua.utdallas.edu/encore/guide.html

4. Find someone with whom you would like to collaborate. I became interested in MOO’s because of the work that Anja Westerfrölke is doing in one, which she spoke about at VJ7.

5. Decide how you collectively want to work with the idea. Anja and I sent each other emails before Digitales to figure out exactly what we wanted to do there. We decided that we would work together to develop a mini-project about archiving and would use the moo as a test place.

6. Work in the open atelier during four days. We worked together to develop and idea, which became what we called digA_p. We tested this idea using the archive material from the previous Digitales. We were open to participation by anyone who wanted to join in and left the archive material on the round table for people to browse.

6. To finish, make a short presentation of the work that you did. We met with Constant and gave them a short presentation about digA_p.

The Play of Archiving

How to participate in a Play of Archiving:

1. Find something that interests you in an archive item.

2. Find someone to share that interest with.

3. Leave a trace of this sharing in connection with the archive item.

How to have an archiving Open House:

1. Choose a date. I chose to have my archiving Open House during the day while my daughter was at daycare. I held the Open House between 9:00 and 17:00.

2. Invite people. I made invitations and sent them by email to about 30 people including students, artists, writers, curators, professors and activists that I know personally. I used Paint to make the invitations and I have a hotmail account that I used to send them. Tip: It’s not usually appreciated to broadcast email addresses so to keep them private put your own email address in the ‘To:’ section and put all of the addresses of your invitees in the BCC (Blind Carbon Copy) section.

3. Make a support for the Play of Archiving to take place. I decided to make a little text explaining the archiving Open House and the Play of Archiving. Then I made booklets where players could write a profile of themselves and could leave a trace of the Play of Archiving in connection with the archive item. I used Paint to make the booklets and the text.

4. Prepare the environment for the Play of Archiving to take place. I set up media stations in my house. The stations were: minidisk station, audio CD station, Video station, text station. The archive materials that I made available at these stations were minidisks, audio CD’s, VHS and DV tapes, books, posters, folders, and texts which I selected from Constant’s Digitales archives. Most of the material was from Digitales 2004, however some of the material was from earlier years. I also made a snack station - this really worked to bring people together to chat.

5. Make the snacks. I made veggies, hommus and tsziki, and also cookies the night before the Open House after my daughter was in bed. You can find recipes for these foods ( or other snacks) at www.vegweb.com.

6. Welcome your guests. I had the text, the booklets and some pens ready for the guests at the front door. It’s also nice to introduce your guests to each other so that they feel comfortable.

7. Let your guests play. I didn’t participate in the Play of Archiving myself, instead I was busy making sure everyone had enough coffee, and knew where to find things, etc.

8. Document the event. I took digital stills with my Alfa ephoto307, which I uploaded to my computer during the day. I also took colour slides: I used my pentax 35mm cameras with Fuji 400 slide film and my digital light meter to read the light.

8. Ask your guests for feedback. I spoke with people about the archiving Open House.

9. Thank your guests for coming. I sent out emails the next day to thank the guests who came and to ask them if I could use the pictures I took of them as documentation.

How to make a prototype Website:

1. Decide how you want your website to function. I wanted the archive to be organised by people, where one could only access the archive material through people’s personal ‘homepages’. I wanted the traces of the Play of Archiving to be linked to the archive material. I also wanted people to be linked together by matching things in their profiles, matching archive items, and Plays of Archiving that they might have done together. I also made a distinction between documentation, which was what I called those items that had not been part of a Play of Archiving, and archive items, which had been part of a Play of Archiving. Finally, I wanted people to be able to alter the description and keywords for archive items.

2. Make a concept outline. This is to show how the website functions. I made a rough drawing, or mock-up, using two fictional players to develop how I could make a Digitales Archives website that had the functions that I wanted, meaning: how could players use the webpages, what should be on the webpages, where the pages should link to, etc. I used a pen and paper to do this, and then I made a digital copy using Paint. You can find the outline in the blog's March archives.

3. Make technical outline. This is to show how the website is constructed. I made a mock-up showing each page of the Digitales Archives website, what information would be on the page, and where the page linked to. You can find the outline in the blog's April archives.

4. Make the graphic design of the website. I worked in collaboration with Arnaud Dejeammes to design the way the Digitales Archives Website would look. We used Photoshop and Paint.

5. Do the html. I used notepad and a WYSIWYG ( what you see is what you get) html editor. I decided to make my prototype using only html, so there is no database or programming behind it. This means that this prototype Digitales Archives website illustrates the idea. The addition of programming and a database are what is needed to make this prototype a working site.

6. Test. I checked the website to see that all of the images were loading and that all of the links worked properly. You can also test the website on different browsers and with different operating systems.

A Play of Archiving:

Why is it called a Play of Archiving? Because the word ‘play’ suggests an exchange. That is what this way of archiving is: an exchange between people (read: bodies) in relation to an archive item. The Play of Archiving is a way (read:gesture) for people to put the meaning they produced for an archive item in connection with that archive item. However, the archive item functions only as a catalyst for an exchange between people, it does not continue to be the focus of the exchange between people. This exchange is a sort of intimacy, where one person approaches another to reveal their memory or interest in an archive item. The Play of Archiving can take place in different spaces, or Venues. The Play of Archiving is portable and can work with diverse archives. The Play of Archiving is a set of parameters, it is not a set of rules. It asks that people use the archive items as part of an encounter and exchange. The Play of Archiving is a distillation of digA_p. The most important way that it differs from digA_p is that the Play of Archiving does not include the position of ‘documentor’, thus the Play of Archiving can be used with existing archives.

The two prototype Venues:

I use the word ‘venues’ to refer to the Open House and Digitales Archives website because they are places in which the Play of Archiving can take place. The Venues are not ‘works’. The Digitales Archives website is the prototype Venue that I propose for the digital archive material. The Open House is what I propose as a prototype Venue for the physical Digitales archive materials. I opened my home for the Play of Archiving as an act of hospitality. Hospitality for me is a feminist act. It is making space for the other. Opening my home was an invitation to an intimacy with the guests by opening my private space.

If the meaning of an archive object is made from the position from which it is viewed (read: person, and all that implicates including education level, nationality, gender, race, etc.) then it made sense to me to make these multiple positions and meanings visible through the Venues. This is why each person who participates in the Play of Archiving must fill out a player profile - a record of such things as age, gender, languages spoken, education level, nationality, etc. This profile is not there to give a context for the archive item. The profile acts as a context for the sharing that will take place during the Play of Archiving. The Play of Archiving is not done to propose a meaning for an archive item but to reveal the meanings produced and the sharing that took place by people in relation to an archive item. The position from which the archive is viewed is particularly emphasised with the website, with which the archive is accessed only through people’s ‘homepages’.

Concepts and tools that relate to my process:

The Stranding Blog:

The blog functioned as a meeting point where I could share my research process with others. By using the blog I learned to make visible my research process. This was very difficult at first because I was reluctant to make my research visible online when I felt that it was unfinished. I was afraid of the sort of intimacy between myself and the reader that could reveal my research process with all of its difficulties. I am still learning how to use the blog.

Collaboration:

Collaboration is essential to my practice, particularly as a feminist process, relating to the development of an intimacy between contributors and making space for each other. Collaboration is a way to work outside of the ‘master discourse’. At the same time, collaboration is a way of working that relates to Constant’s openness that I spoke about earlier. I do not think that a collaborative process has to be one of consensus, where each person agrees to create one finished ‘product’. I think that collaboration can be people coming together to work on a project at a particular point in time, or on a specific part of a project, while they continue to develop the project separately.

The open atelier during Digitales 2004:

The open atelier held in the resource centre at Interface 3 (a training centre for women using new technologies) was my first collaboration with Anja. It was also an opportunity to meet the people who have contact with the Digitales archives, such as the employees and students at Interface 3, and the people who attend Digitales. Finally, it was another opportunity to make my research process visible in a different public encounter than the blog.

The MOO:

The MOO was a possible Venue for archiving that I wanted to explore. In a MOO written language and ‘objects’ are the same thing because a MOO is text based. I was interested in this because it was possible for people to ‘handle’ language. I thought that this could be particularly interesting for the text-based archive items because of the metaphor of the body in ‘handling’ the language. The MOO was interesting and I think that it holds a lot of possibilities, however it takes a lot of time to learn how to use it. I felt that this would make the Digitales archives rather inaccessible, and so I decided to work with other Venues. I am continuing to work in the MOO for other projects.

The Digitales archives:

I work on gathering the traces for the Digitales archives because it gives me an idea of the content of the archives, as well as the process for gathering the content for the archives. It is from working on gathering the traces that I thought about the difference between documentation and archive material that I spoke of earlier.

Respondent at VJ7:

I was a Respondent during the VJ7 seminar the Lining of Forgetting in November and I found that it was a great way to focus and develop my early research. I developed questions that related to my work for the seminar and for the subsequent interviews that I did.

Interviews:

The interviews functioned as part of my process much in the same way as being a respondent for VJ7, by helping me to focus and develop my work. The interviews also helped me to ground my work in current art practices. Finally, it was my interview with Anja that led to our collaboration.

The Publications:

The texts that I did for publication ( Scenario for an Archive Discussion for the VJ7 Catalogue and Conversation with a Robot about Archives... for the Transmedia Text Series 03) made me focus the presentation of my practice. I worked collaboratively with Arnaud Dejeammes on Scenario for an Archive Discussion. These texts were a way for me to learn how to develop and communicate my practice in a finished presentation.

Selected Bibliography

Aristarkhova, Irina. Virtual Chora: Welcome. http://www.aristarkhova.org.

Bernadac, Marie-Laure and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, eds. Louise Bourgeois: Deconstruction of the Father,

Reconstruction of the Father. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998.

Carnegie, Elizabeth. ‘Trying to Be an Honest Woman: Making Women’s Histories’. Making Histories in

Museums. Gaynor Kavanagh, ed. London: Leicester University Press, 1996.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art and Society. Third Edition. London: Thames and Hudson

Ltd, 2002.

Cooper-Greenhill, Eilean. Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture. London: Routledge, 2000.

de Certeau, Michel.‘L’espace de l’archive ou la Perversion du Temps’.Traverses: Revue du Centre de Création Industrielle, Vol 36. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1986.

Dekoven, Marianne ed. Feminist Locations: Global and Local, Theory and Practice. New